Movie Magic: "A Kind of Language" at Fondazione Prada

Words by Annalise June Kamegawa

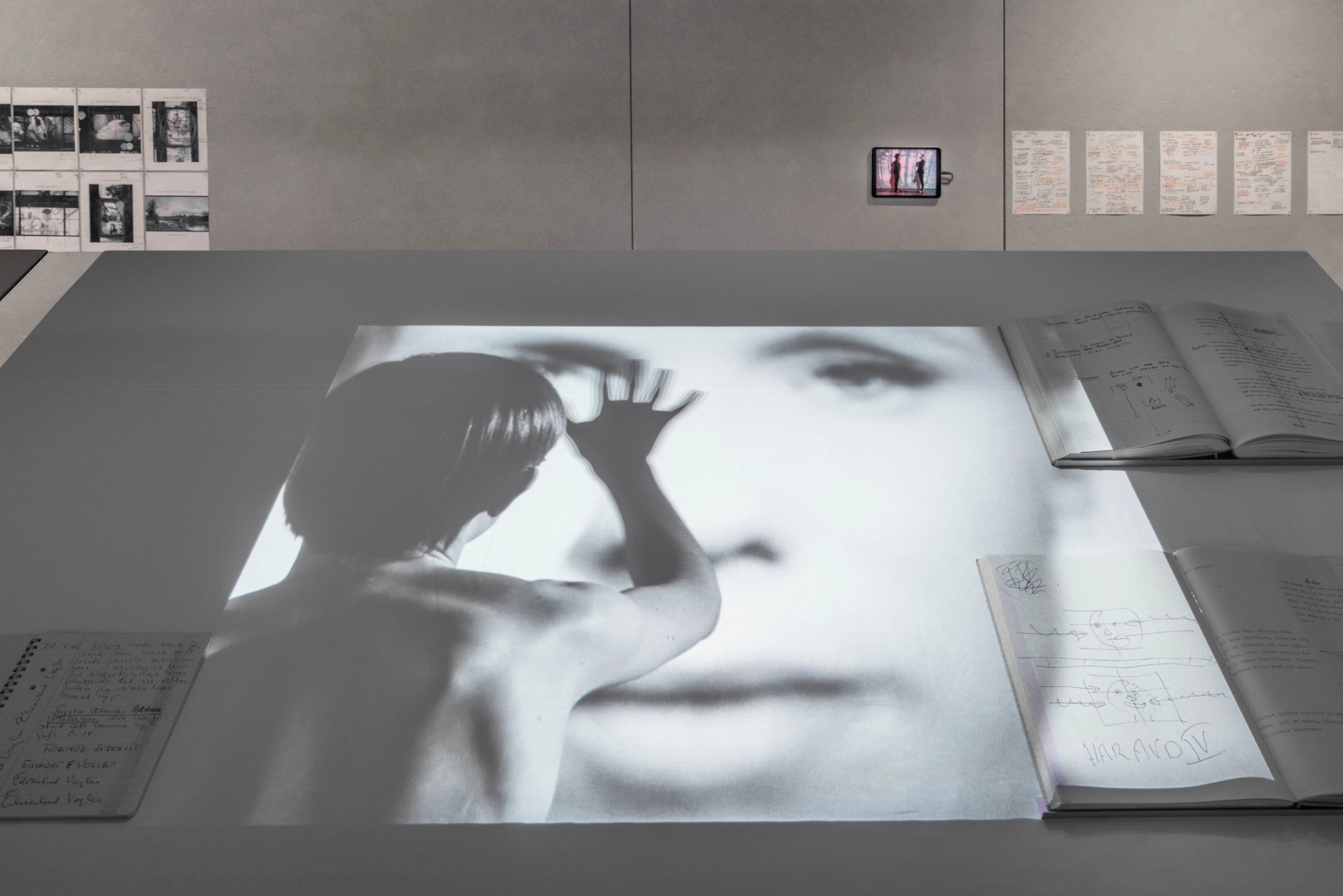

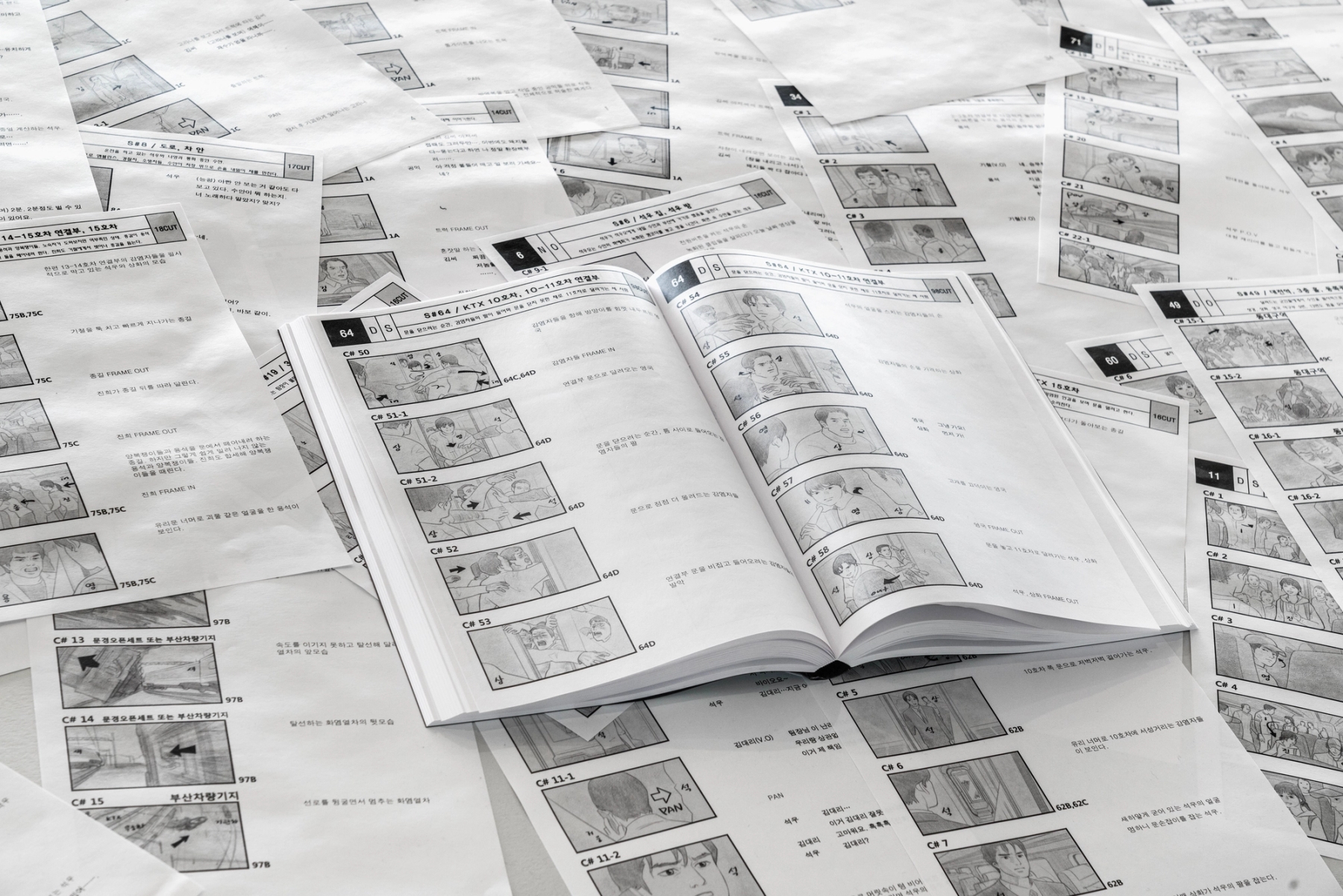

Exhibition photos by Piercarlo Quecchia @ DSL Studio, courtesy of Fondazione Prada

Melissa Harris, curator of "A Kind of Language," running from January 30 to September 8, 2025 at Fondazione Prada's Osservatorio, has had a long-time relationship with the captured image. For many years, she worked at Aperture Magazine and is now an editor-at-large for the publication.

In conversation with Novembre, she remarks on her approach to storyboards, the central object in the exhibition, saying "Going from still to moving is not the kind of shift you might imagine because for me, it's all about storytelling. And I don't mean storytelling in the sense of fiction or non-fiction. I just mean moving through a narrative. Storyboards do that too — they're really a form of narrative, plotting out something in process."

I visited Fondazione Prada's Osservatorio in the late afternoon to see the exhibition. The afternoon light was filtering in from the glass ceiling of the neighboring Galleria Vittorio Emmanuelle II. In moments like these, I can't help but become a bit intoxicated by the glamor of my job: indulging in the arts on a Tuesday afternoon while someone else is balancing Excel spreadsheets in a neighboring skyscraper. Not to say that I don't also chase email threads and battle editors over syntax, but I also want to confirm that there are parts of this job that do fit quite snugly into the character that one Ms. Bradshaw brought to screen in the late 90s.

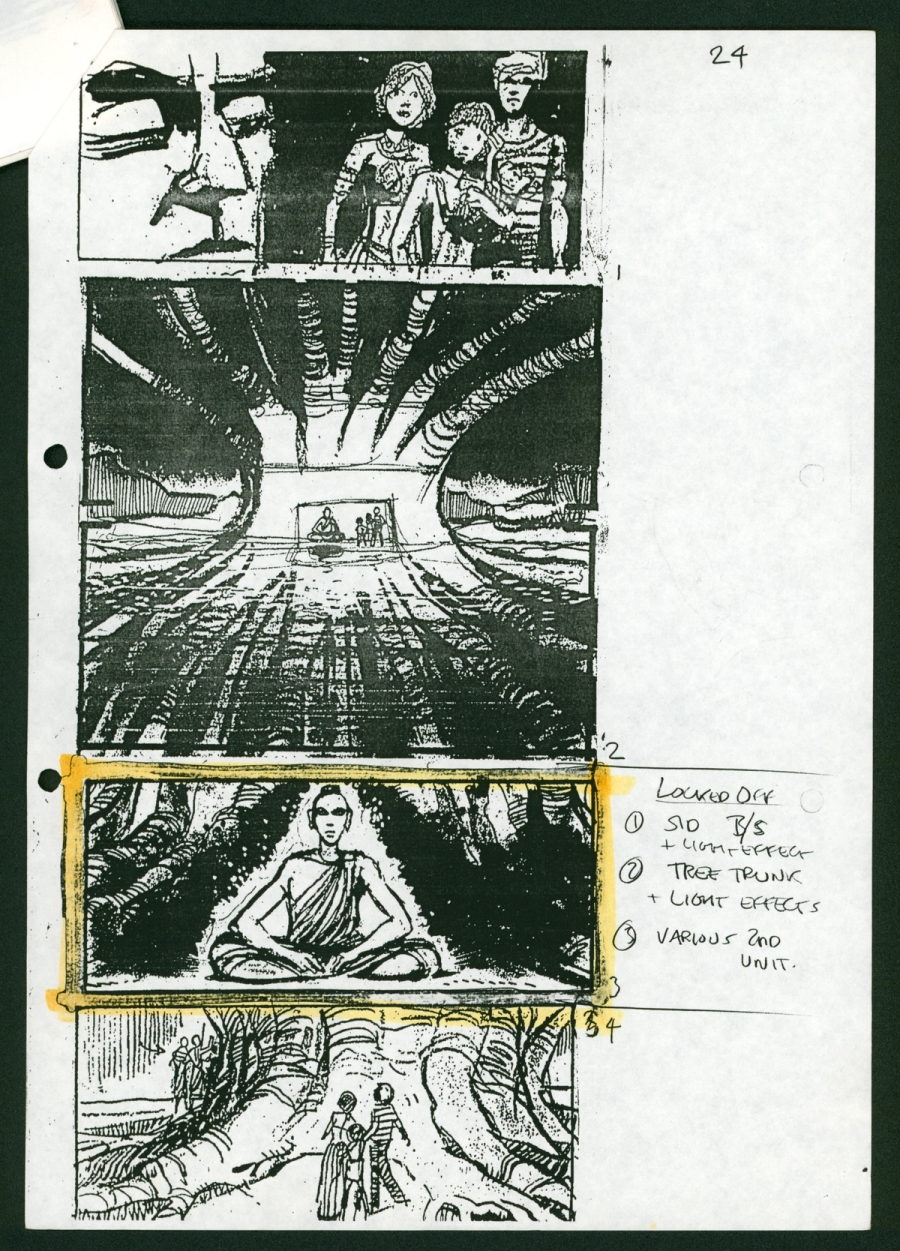

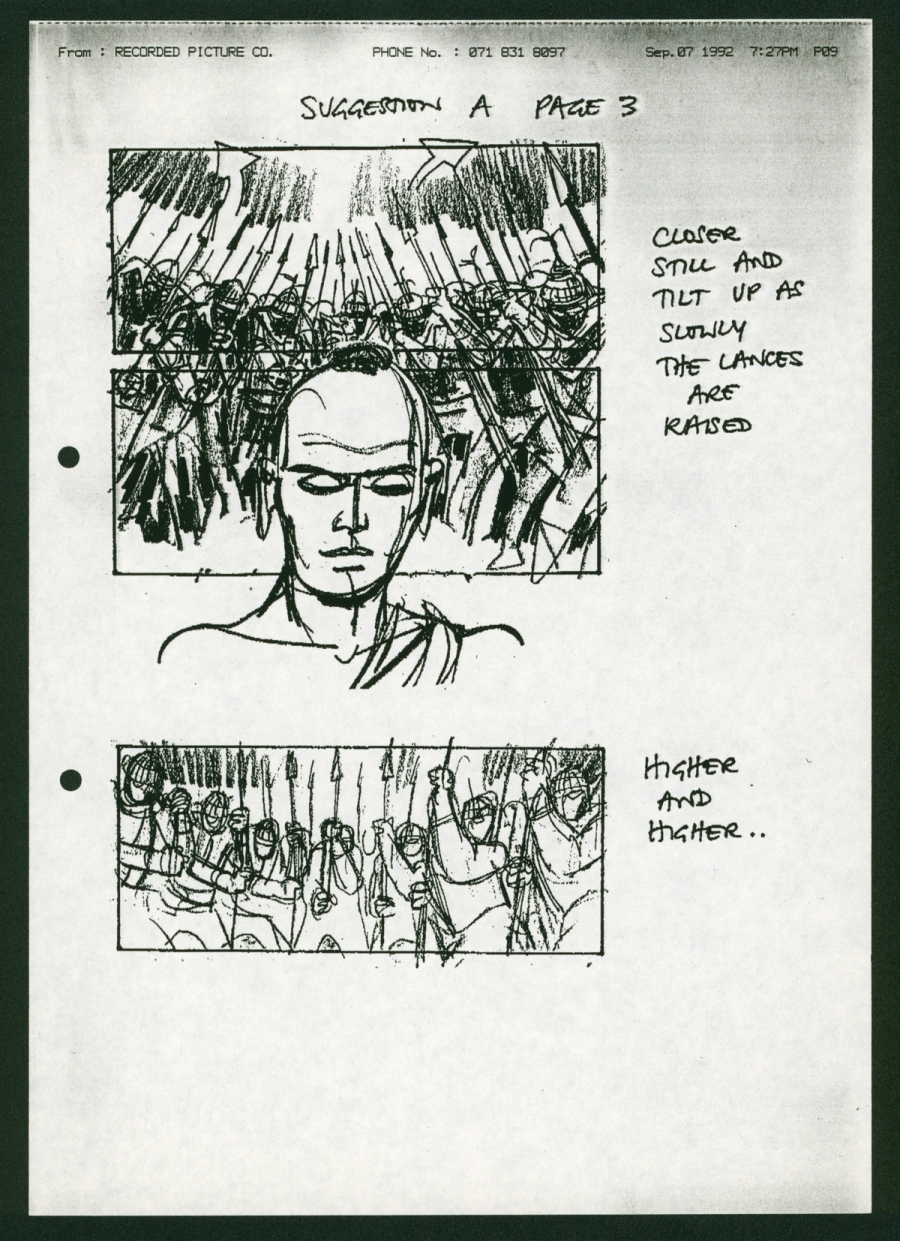

In A Kind of Language, early storyboards from Terry Gilliam's similarly journalistic adventure Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas are drawn in the same bulging perspective that has become iconic of Hunter S. Thompson's odyssey through the desert. While I lack the stamina or tolerance to step into the shoes of Raoul Duke or Dr. Gonzo, I do find it flattering how, on the silver screen, journalism is granted such multitudes and sex appeal. What a waste of budget it would have been to show Johnny Depp hunched over, line-editing his work. Through the beautifying lens of film, work can — and should — be psychedelic, an adventure, a perversion of its very banality.

But don’t movies also do this to themselves? In their neatly cut run times, the labor of

filmmaking all but disappears. It’s one of the core "magics" of movie magic: the ability to create a product that, in its very nature, suspends disbelief and hides its commercial underpinnings with artful ease. Within these storyboards, the planning of this labor—all the casts, crews, production efforts—comes back into clear view.

When reflecting on the demystifying nature of storyboards with Harris, I mentioned how I couldn’t shake the tension between filmmaking as an art and as a commercial investment. Seeing that she had been deep in the collection of these storyboards, I asked if she felt that tension in these early proof-of-concepts.

She remarked with ease, “Despite the fact that these films eventually enter the market, the storyboards themselves don’t feel tied to that. Most of the people who had them weren’t keeping them for any commercial purpose. They weren’t selling them. Half of them couldn’t even find the boards right away.”

I could feel my eyebrow raising to her response and, to address my monetary musings, she adds, “there’s a creative value placed on them, absolutely. But not a monetary one. And I love that. It was refreshing. I didn’t feel any commercial constraints when looking through these storyboards.”

She went on to talk about how teams, “were Xeroxing them, faxing them, mailing them, and pinning them up to a gazillion different walls. They were being shared, handed out, and stepped on. . . .”

In the exhibition, you get the sense that you are looking at something that is more artifact than art. Most of the storyboards are replicas that show where the original was once folded or torn. This adds to the feeling that you’re not in your typical art exhibition where the originality of a piece, its ‘one and only’-ness is what gives the event its aura.

Instead, the display of these storyboards, with all their flaws intact, show their provenance. It doesn’t hide its transmission, but celebrates it, bringing into conversation the reason they were created in the first place. When sourcing the storyboards, Harris said, “For the most part, we asked for very high-resolution, true-to-size scans.” Highlighting how, “We didn't need the originals and people were more likely to share them with us if we weren't asking for the originals. Most of the time, these storyboards weren’t made solely for the filmmakers to work out their own ideas—they were made to communicate with a large team. So we thought: let’s do it the way they did it. Let’s follow their lead.”

There was a “philosophical” benefit to this decision, but also an undoubtably logistical one as well. Her process, which took over two years, was a globe spanning research effort. Not only was she aided through associate curator Carlo Barbatti at Fondazione Prada in Milan, but she developed a network of filmmakers in India, Asia, and across the western hemisphere.

Although the breadth of filmmakers was wide, her research method was still intimate, in the way that you imagine a seasoned journalist would operate as they build a story. It involved finding people, “through a dog walker who worked for a filmmaker, through a nanny...” She even found herself knocking on her neighbor’s door— Pixar filmmaker Andrew Stanton—striking up a conversation through their dogs’ mutual friendship.

The exhibition really contains a breadth of creative voices because Harris and her team were keen to represent the industry as it really is. “We worked really hard to find women for the show. It’s not that there aren’t female directors out there. There are. But not all of them make storyboards… so it wasn’t a matter of overlooking people; it was, again, can I reach them? And if I can, did they actually make storyboards?”

They succeeded in their effort. Not only did they show mainstream filmmakers, but they also included a variety of women who had experimented with moving image. “I had Sofia Coppola, Yang Lina, Jia Ling, Sally Potter, and Agnès Varda. But we also looked beyond the traditional film world and into the art world. That’s how we brought in individuals like Joan Jonas, Carrie Mae Weems, and Ericka Beckman. But I think it still remains a tough time for women filmmakers, although it's certainly better than before."

Despite, or better said because of, the impressive lineup of filmmakers, Harris made a clever decision that allowed, not the director or writer to speak at first, but the storyboards themselves. When displayed, the storyboards are not obviously marked by film title or director. The viewer has to approach the images, move through each frame before finding the film’s detail tucked into a small exhibition label on the corner of each display.

"I'd love to say it was a deeply intellectual decision," remarked Harris with some candor, "but honestly, it started as a design choice. That said, I suppose it was both. The idea was to give you this immediate, visual hit first. I wanted people to really see the work before being told what it was part of."

In this coyly labeled state, these storyboards not only have their own identity, but they reveal the inner working of these creatives barring our own preconceptions that we’ve developed through their celebrity.

There are Iñárritu’s detailed storyboards, created by Edgar Clement, that look straight from a graphic novel. There are Sofia Coppola’s sketches for The Virgin Suicides that may as well have been done on a napkin – looking precisely as how one would imagine Coppola’s girlish narratives to take form as pen drawings. Then there’s Todd Hayne’s storyboards, created by the director himself, that, at risk of discounting a director’s ability to also be a visual artist, are actually quite impressive.

"The context is there — you can find out which film it's from, who made it." Harris says, referring back to the little museum plaques.

"But I wanted the first encounter to be with the image itself. To experience the storyboard as a drawing, as a piece of visual thinking, not just as a reference to a finished product."

"In a way, it was also about individuating the work. Letting it stand on its own, and showing how evocative these storyboards can be — how much they communicate on their own before you associate them with the ultimate product."

The audience also gets to see all the artists and players that will eventually need to fill out this skeleton of the film. Sometimes it looks like the film was willed to life, an apparition from scrawled notes, as is the case for Salvador Dali’s drawings and handwritten notes for Luis Buñuel’s short surrealist film Un chien andalou. In other cases, like the unfolding pencil-drawn tryptic for Snow White that rivals the beauty of the finished film, you understand that these are more than art, they are part of the production process.

“Before there’s any footage—especially before the digital era, when things were much more expensive—you really had to plan.” In the exhibition text, Harris notes how storyboarding in animation was adapted into mainstream filmmaking practices because of its usefulness.

"Film was costly. Multiple takes were costly. So the storyboards were very utilitarian. And I actually love that about them. I think that's what's so interesting:

They're not just aesthetic objects, they represent a kind of planning and committment.

They carry the weight of the investment — not just financial, but also the investment of time and talent from the costume designers, the set designers, the lighting people. That whole collective effort starts to come into focus through these boards. You can see the collaboration beginning."

What stuck with me in our conversation was Harris saying that,

"This wasn't meant to be a precious show — it was a work-person's show."

There's something humble, even reverent, in the way A Kind of Language frames process over polish. You feel the work, and the people behind it.

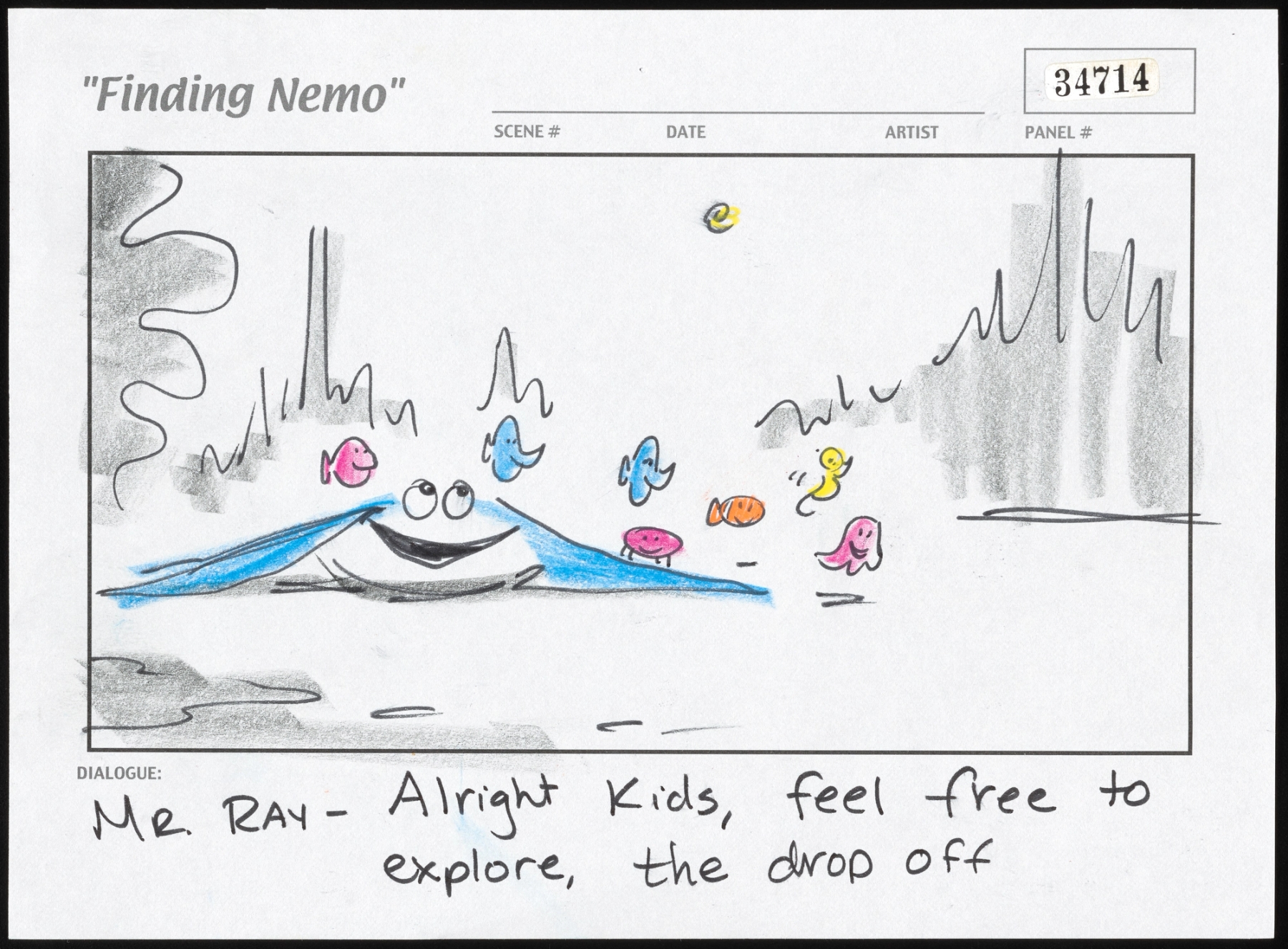

Take, for example, the early drawings for Finding Nemo on view. Pixar is no stranger to budget pressures. As Ed Catmull writes in Creativity, Inc., “Each investor was going to have its own agenda, and that was the price of our survival.” referencing the struggle to secure investing for the expensive, sophisticated computers they would need to create their first animated films. It’s a reminder that most every artistic vision sits within financial constraint. The idea that Dory and Marlin’s entire underwater odyssey might have been shelved for lack of funding—that “Fish are friends, not food” might never have existed—is quite devastating.

When I asked about Finding Nemo's storyboards, Harris bumps up against my gut reaction by saying,

"In the drawings themselves, I don't see that commercial pressure. What I see is someone working through a charming story — about a fish.

I don't see notes like, 'We have to do this because otherwise it won't sell.' What I see is: how are we going to make this great? How do tell the story? How do we render these characters — make them sympathetic, or villainous, or whatever they need to be?"

Knowing Catmull’s early struggles, I couldn’t help but read the Finding Nemo storyboards through a monetary lens. Each frame—neatly printed templates, filled in by hand with colored pencil—seemed to be making a case for itself. The sea creatures, in their primitive, slightly clumsy forms, were already endearing. But more than cuteness, what I saw in the precisely organized and ordered panels was a kind of hustle: a visual plea to prove that this story was worth the investment. Some part of me thought, it’s because Pixar needs an ROI!

My thoughts zeroed in on the logistics, the cost, the budget behind it all. Because when I see labor, I also think of money. I think of compensation. One doesn’t exist without the other. In these early, vulnerable sketches, there’s a sense of uncertainty as the story is worked through that I interpreted as a kind of planning both for budget and what looms ahead.

Harris told me that getting filmmakers to share their process was a concern at first.

"Not everyone wants to share their process. That's a really intimate thing. Once a film is finished, it's out in the world — it's public. But your process — that's something you often hug tight to yourself."

Many creators agreed to contribute to the exhibition, leading Harris to remark, "So the fact that everyone was willing to share that with us — it was incredibly generous."

What these boards reveal—so often invisible in the polished final cut—is the messy, deeply human effort that conjures movie magic. They show the vulnerability of beginnings, the leap of faith it takes to believe that an idea can become a film. It's a reminder that before movies can suspend disbelief, they begin with belief: in the story, in the image, in the idea that all this work might just reflect something essential back to us on the silver screen.

Harris's reflections on creators' generosity, intimacy with process, and her soft spot for a charming story about a fish snapped me back to the core of art making. The commercial art — films, yes, but also fashion, architecture, anything where aesthetics and intention are inseparable from their market presence — give us commodities with a funny value metric. These aren't just goods optimized for labor costs and margins. Their success isn't measured solely by buyers, units sold, Rotten Tomatoes scores, or New Yorker reviews. It's also about whether they resonate — whether they've managed to say something that speaks to its audience in its own unique way.